To help commemorate National Public Health Week 2025, this publication is part of a series that explores policies, programs and considerations to improve population health.

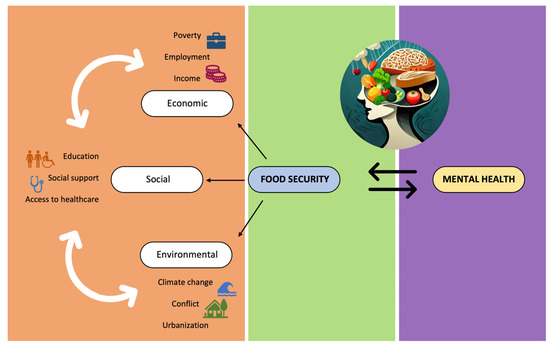

An individual’s wellness, or state of being in good health, is supported by a variety of factors, including economic stability, neighborhood and built environment, and education access and quality – factors also known as social drivers of health (SDOH). Food insecurity, as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), is limited or uncertain access to healthy and safe foods, while food or nutrition security indicates access to enough food for an active and healthy life. Nationally, 47 million people, including 14 million children, are food insecure. Of those, historically marginalized populations often experience disparities around nutritional access and choice compounded by SDOH. Although evidence points to nutrition as a vital contributor to overall wellness, many populations face barriers compounded by SDOH in seeking to access healthy or nutrient- dense foods.

Food security and insecurity are measured in ranges, with low and very low food security indicating reduced diet variety and nutritional quality as well as disrupted eating patterns like skipping meals. Those with low income, who are geographically isolated, or who have limited access to quality education are more likely to experience food insecurity, directly impacting wellness. This commentary explores health and childhood development implications of food insecurity, federal assistance food security programs, and innovative approaches to increase access to nutritious foods for all populations.

Food Insecurity and Associated Implications

In 2020, 13.5 million people lived in food deserts or communities with limited access to grocery stores or supermarkets in the U.S. Food insecurity manifests in various ways throughout the country’s regions, cities, and states; unique social drivers also increase access barriers, ultimately impacting population health. While food insecurity trends fluctuate in urban and rural areas nationally, households in the southeast region of the U.S. experienced the highest rate of food insecurity in 2023 at 14.7% compared to the national average of 13.5%. Living in communities with scarce public transportation, elevated poverty levels and limited access to quality education can impact one’s ability to access healthy food and make informed nutritional choices , increasing food insecurity risk and the likelihood of poor health outcomes.

- Diet-related chronic conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, asthma, and strokes, are commonly associated with food insecurity. Lower food security can increase chronic condition prevalence and associated healthcare costs.

- The complex relationship between nutrition and mental health is reinforced in a 2021 study where low-income food insecure adults screened at around three times more likely to experience depression, anxiety and high perceived stress compared to low-income food secure adults.

Childhood hunger can have profound impacts on lifelong well-being. Children living in poverty, around 10 million in 2023, are more likely to experience some form of food insecurity. In that same year, about 14 million children lived in food insecure homes, reinforcing conclusions drawn that hunger and federal poverty levels are not always connected.

Hunger can exacerbate existing stress borne by vulnerable populations. Hunger, like homelessness or exposure to violence, is categorized as an adverse childhood experience (ACE) or potentially traumatic event, commonly tied to poor emotional and health outcomes later in life. Hungry students often struggle to focus, make friends and regulate their emotions in academic settings. The impact of food insecurity can also be seen in the early moments of a child’s life, years before they step into a classroom. According to Zero to Three, 1 in 7 households with a baby experiences food insecurity. Additionally, infants and toddlers exposed to food insecurity are more likely to experience low birthweight, poor cognitive or physical function, or hospitalization when compared to food secure peers. This reinforces research indicating even short periods of childhood food insecurity can directly impact childhood health, behavioral issues and academic readiness.

Food Security: Making Nutritious Food Accessible to All

There are several longstanding programs operated in partnership between states, territories and federal agencies to combat food insecurity nationwide. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest national program that serves low-income families and individuals of all ages. Many related programs, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Child and Adult Food Care Program (CACFP); National School Lunch Program (NSLP); School Breakfast Program (SBP); and Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer (S-EBT) specifically target children and families. Some programs offer direct food purchasing assistance, like money on an EBT card, that allows consumers the flexibility to buy a menu of food items at their preferred retailer. Other programs, like the National School Lunch Program and Child and Adult Food Care Program, provide benefits to community-facing organizations to enable those organizations to serve food directly to specific populations, like in-school meals.

Federal Programs that provide purchasing power to consumers include:

- SNAP provides direct food purchasing assistance via an electronic benefit transfer or EBT card to low-income households.

- WIC offers nutritional support and food vouchers for pregnant women and young children.

- Summer EBT helps families manage increased food costs during summer breaks through additional EBT benefits.

Federal Programs that provide benefits to community-serving organizations include:

- CACFP ensures access to nutritional meals and snacks in child care, after school, or adult care settings.

- NSLP and SBP help schools provide free and reduced-price meals to students during the school year and during school breaks.

Governors’ offices continue to maximize the impact of federal programs, create state or territory-based food insecurity solutions, support local farmers, and limit access barriers. Food security programs aimed at reducing transportation needs, supplementing financial burdens, and promoting nutrition education mitigate social drivers of health and their impacts on population access and health outcomes. Related approaches acknowledge research illustrating diverse populations experiencing food insecurity and the need to integrate culturally appropriate information and community partnerships in program development and implementation.

- Operating in 49 states (e.g., Maryland, Montana, Nevada and Wisconsin), the Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program is a component of WIC that aims to lessen transportation barriers and increase nutritional choice. Administrative agencies allocate money, produce educational resources and develop farmers’ market directories for recipients to purchase fresh fruits and vegetables at local farmers markets. Federal funds support all food costs and 70% of program administrative costs.

- USDA partners with tribal-serving organizations in administering the USDA Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiative to promote culturally appropriate food access (e.g., Indigenous Food in School Meal Programs, Indigenous Animals Harvesting and Meat Processing Grant) and nutrition tailored to American Indian and Alaska Native dietary needs.

- The Senior Farmer’s Market Nutrition Program is another population-specific food security program for low-income adults 60 years and older, administered in 57 agencies in states, territories and federally recognized Indian Tribal Organizations. This program increases access to locally grown fruits, vegetables and herbs through farmers’ markets, roadside stands and community supported agriculture programs.

- Farm to Child and Adult Food Care Program operated in states, including North Carolina and Virginia, increases access to state-grown healthy foods for children and adults. This program links participating care and education facilities to local farmers and food producers through incorporating locally grown food through meals, nutrition education, tastes tests and gardening opportunities.

State Programs

Outside of federal funding, some states and territories are pursuing opportunities to create programs supported by general fund dollars.

- In February 2025, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee proposed a state investment that would provide a one-time payment of $120 to eligible children enrolled in SNAP and Temporary Assistance for Needy Family in counties that are un- or under-served by the federal summer food program

- In January 2025, Delaware Governor Matt Meyer signed Executive Order #5, which established the Delaware Council on Farm and Food Policy with a charter to create a cross-agency strategy on food security to address system gaps and improve nutrition statewide.

NGA Support

NGA is tracking food security trends at the state and federal level and acknowledges potential federal funding changes that could impact the reach of available programs. The NGA Center for Best Practices will continue to publish resources, support technical assistance requests, and host interactive webinars to cultivate a platform for subject matter experts and NGA members to share experiences and best practices . For more information, please contact Jessica Kirchner (jkirchner@nga.org) or Asia Riviere (ariviere@nga.org).

This publication was developed by Asia Riviere and Jessica Kirchner with the National Governors Association Center for Best Practices.