A top Let’s Get Ready! priority is measuring what works – and what doesn’t.

There are plenty of bright spots in the “what works” category, several of which were represented at a recent initiative convening in New York City. Innovative schools, programs and organizations are succeeding – raising test scores and helping students of all backgrounds find pathways to career success. It’s by understanding and replicating those models – while adapting them for each state’s unique needs – that we can identify innovative ways to redesign and strengthen the nation’s education system, to ensure that each student, and the American economy, succeeds.

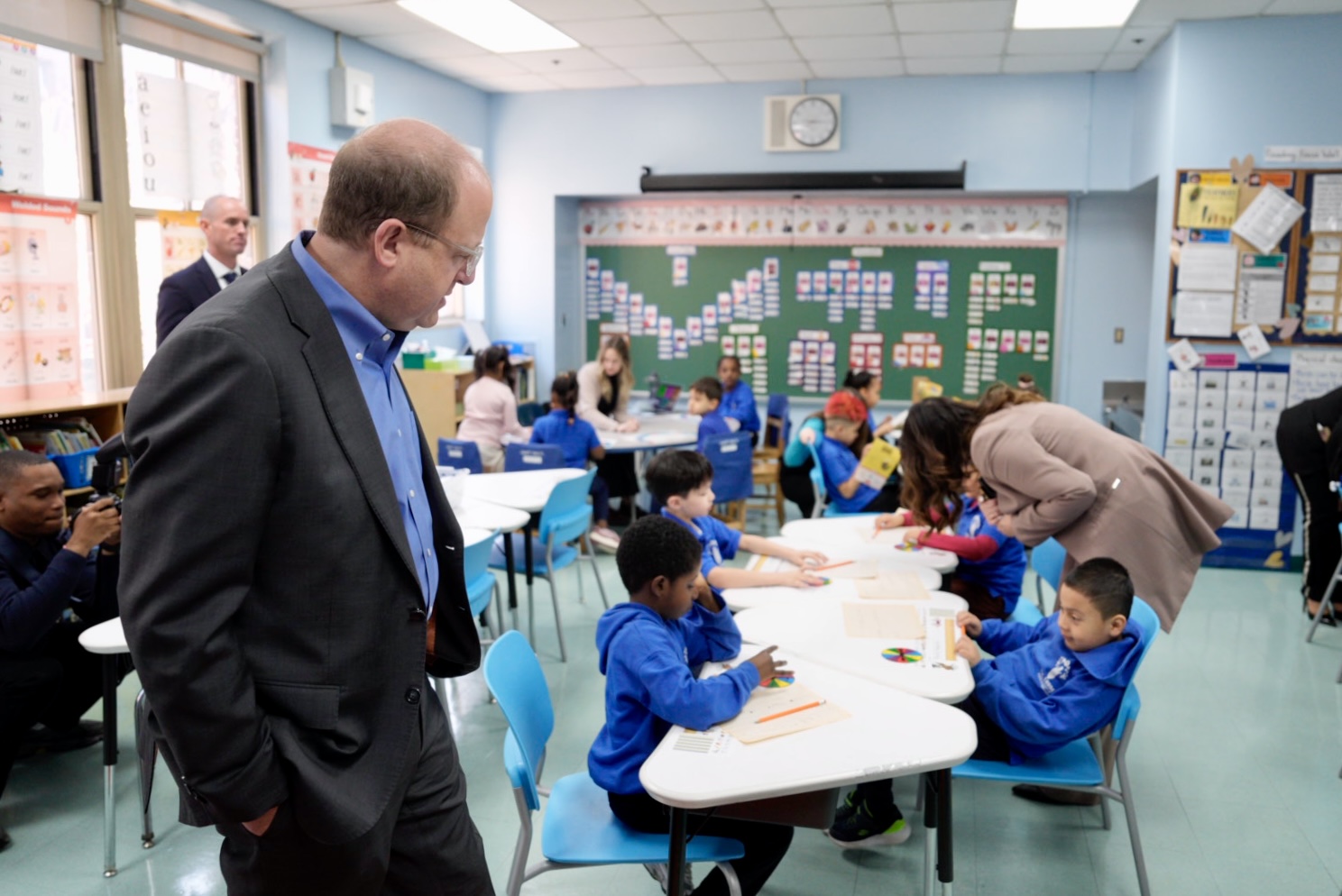

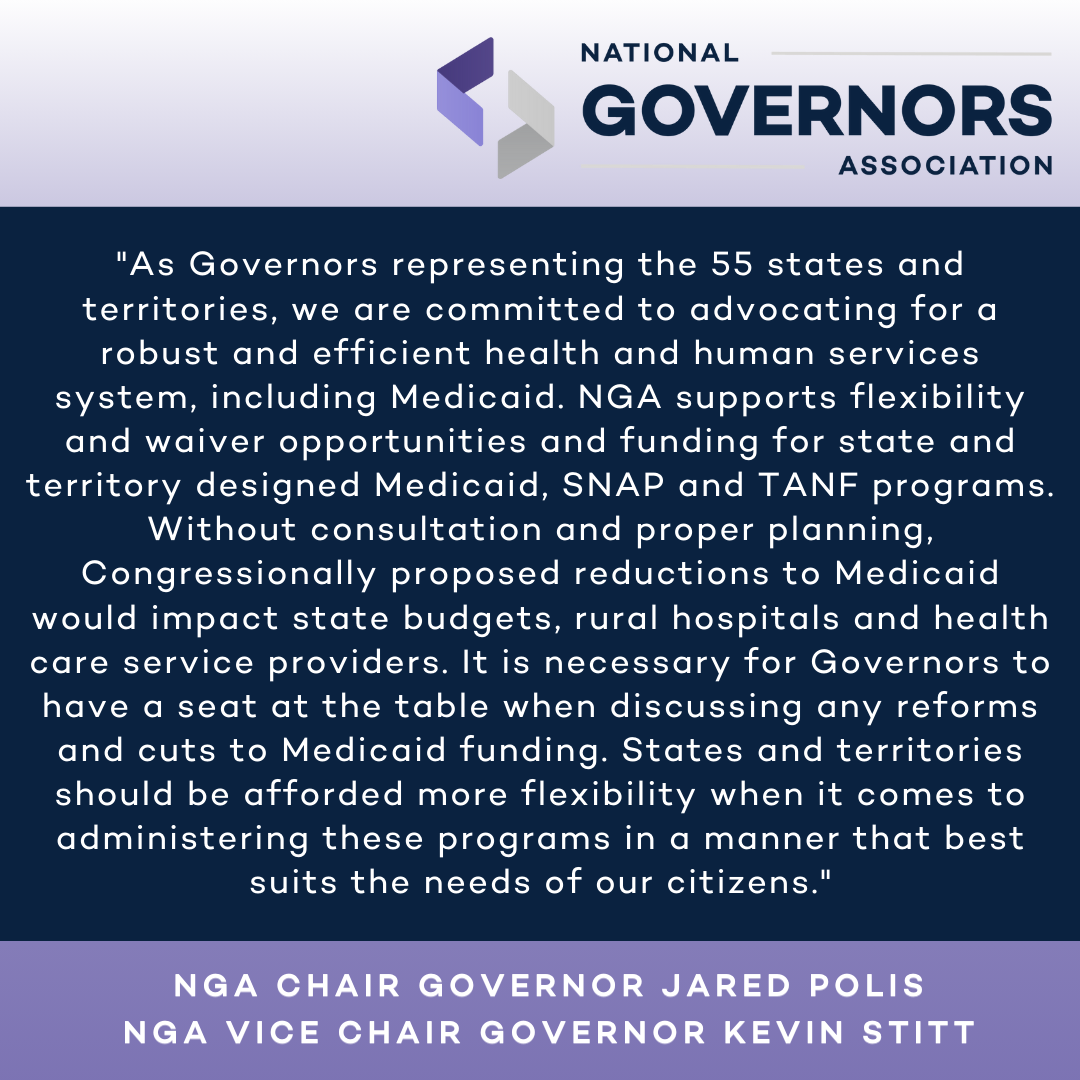

“We’re taking a deeper look at the education to workforce pipeline,” said NGA Chair Colorado Governor Jared Polis. “We want to explore what we’re learning in workforce training and technology to help us prepare students for success – and, of course, focus on what role states and Governors can play.”

Governor Polis welcomed an expert panel to explore how to better define and measure educational success beyond standardized tests, which factors contribute to student achievement, and how technology can help.

Panelists included:

- Dr. Tequilla Brownie: CEO of TNTP. Through personalized consulting and community engagement, TNTP partners with schools and systems to design and deliver innovative solutions to help students access the factors of mobility that will help them thrive.

- Dr. Stephen Moret: President and CEO of Strada Education Foundation, whose mission is to help clear the path between education and work by fostering collaboration between the institutions that serve learners, and the employers who need them.

- Shalinee Sharma: CEO and Co-Founder of Zearn, a nonprofit educational organization behind the top-rated math-learning platform used by one in four elementary school students and by one million middle school students nationwide.

- Moderator, Scott Pulsipher: President of Western Governors University, the nation’s first and largest competency-based university. WGU’s focus is to reinvent education and workforce systems to support success and economic mobility for every student.

Dr. Tequilla Brownie, TNTP

“At TNTP, we believe that we need absolutely outcomes, data, metrics. Unfortunately, [in the U.S.] we have narrowed that to a narrow set of outcomes, largely around only standardized tests. Are they key? Are they important? Yes. But we have to define what success is, and then map our way to that and hold ourselves accountable to that.

“In our research Paths of Opportunity, we found that young people across the country coming from poverty had only about a 30% chance of experiencing a living wage by the age of 30. And to be clear, a living wage is the floor, not the ceiling. Our highest-performing students only had about a 58% chance of getting to a living wage. That means our best and brightest from poverty had the toss of a coin’s chance of getting to a living wage by 30. That tells us that academics did increase the chances for kids from poverty, absolutely. But it also showed us that academics in isolation is insufficient.

“We sit at the intersection of research, policy and practice. As we start to look at our own data, and hear from the millions of students we serve, five themes emerge for us. We call these our Five Factors: academics, social capital, career-connected learning, personalized supports, and civic and community engagement. Those factors do not work alone. We’re not proposing silver bullets. They are all inextricably linked with one another.

“We [can’t] leave it to chance that young people have a plan, have a path, and are on that plan. Higher ed has figured out [personalized supports] with the advising model. We don’t leave it to chance for college students. Why on earth would we think that young people in our K-12 systems have the skills to navigate on their own?

“The true question is: How do we ensure that young people have multiple options and multiple pathways? That optionality can’t start in high school. We can’t think that they’re going to magically wake up on their 16th birthday ready to engage in apprenticeships, [while] they’re reading at a second grade level.”

Dr. Stephen Moret, Strada Education Foundation

“One of the great things about America is that we support multiple pathways to opportunity. If we think about which pathways most consistently lead to a good job and a good economic outcome, you can make a pretty strong case that the number one is quality apprenticeships. Number two, is a close call between applied associate programs in community colleges and bachelor’s degrees and above.

“The last path, which is probably the most interesting and the least understood, is the non-degree credential space.

“If I had to pick three things [for states to measure], I would say one is making sure that you are actually tracking the data that you need in the unemployment insurance and wage records, including title or occupations. The second is tracking outcomes for non-degree credentials, which almost no states are doing today. Most employers are already tracking this data; it’s just a matter of reporting it along with the rest of their UI data. Third, you can’t just collect the data; you need to have a dedicated team of people to analyze and build expertise in it, not only to understand what the data is saying, but to engage directly with real employers to get a qualitative perspective as well. No state has nailed all three just yet.

“I had the opportunity to participate in a few thousand site selection decisions of companies. One of the things that I found during that time was that talent really became the dominant factor. Taxes matter, incentives matter, site preparation matters. But if there’s ever a silver bullet in economic development, it’s talent. What I was hearing from the companies was so different from what the higher education story was – not in any sort of intentional way. They just weren’t talking the same language. Finding ways to help them understand each other better would be great for everybody.”

Shalinee Sharma, Zearn

“Before founding Zearn, I worked in the business world and [defining success] was simpler. It was just: As a company, am I going to put my plant or my distribution center in this place? Can I find a workforce? If no, then I will not. I worked with companies making those decisions, and the quality of workforce, and the belief that there was a workforce pipeline, was critical part of that decision.

“At the minimum, we should be thinking about these important benchmarks, which are: When our students finish K-12 and/or a CTE credit and/or a college degree, are employers excited to hire them? And I can tell you, sadly, one of the reasons I left that world and came to K-12 was that employers were not happy with the quality of our students. Do I want more for my own 14-year-old twin boys than an employer is happy with them? Of course. But that is the threshold we have to be hitting. We need to be steering and focusing on that.

“Technology is neither good nor bad; it’s just a force multiplier of whatever the human intent is behind it. The most important thing that technology can do is something that our systems don’t do today, which is [serve as a] catch-up system. The way K-12 works today, particularly in math, is if you fall behind, you are behind. We want every one of those kids to catch back up, be successful, contribute to our prosperity, contribute to our country. So we need to give every kid more chances. And that’s something exciting and new that technology can offer.

“Sometimes when we talk about education problems [as] insiders, we depress everybody else, and that’s really dangerous because people give up on us. We are literally creating the future of this country, so we can’t have people give up on us. The reason I say that kids can catch up is because they can.”

Scott Pulsipher, Western Governors University

“We’ve certainly discovered in our work at WGU that if an individual does not have a sense of how they are going to contribute to the world, what we like to call a ‘vocational identity,’ they won’t attach a purpose to their education. It has to have something to connect to how they see themselves contributing to the world.

“The competency-based approach to education says you have to have proficiency established against skills that are needed in the workforce. If the talent development pathway is not producing that, you got to rethink how you’re doing the development of that talent.”

New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy

“We spent a lot of time on our Economic Development Authority trying to figure out where to jump start apprenticeship and workforce development programs, and in what sectors. It’s the bridges that we don’t build, which I think are as important as the ones we do build. In New Jersey, I’d like to think we could make cars and trucks again. But the manufacturing that’s much more in our wheelhouse is sophisticated pharmaceuticals, fuel cells for solar energy, things that [are] very much STEM-focused. If you’re not careful and selective, you could be banging your head against the wall on a bridge that, frankly, is an unnatural bridge for you.

Rhode Island Governor Dan McKee

“In trying to connect our higher ed with our K-12, and to connect certificates or two-year or four-year [degrees], we are trying to track the income as results from that. I really believe in dashboards. We can track attendance. I can track what we’re doing on municipal road improvements. And the dashboard we haven’t figured out in this road to prosperity is the dashboard tracking all the work that we’re doing, which we believe is going to get results. We are seeking out a way to take the work we’re doing on apprenticeship programs, pre-apprenticeship programs [and other policies] [and link it to outcomes.]”

Learn more about the initiative here, and watch the full session below.