This brief focuses on emerging trends in raise-the-age efforts across states, including: (1) raising the maximum age of juvenile court jurisdiction beyond 18, (2) raising the floor, or minimum age, at which a person can be processed through juvenile courts; and (3) amending the transfer laws that limit the extent to which youth and young adults can be prosecuted in adult criminal court jurisdiction.

(Download)

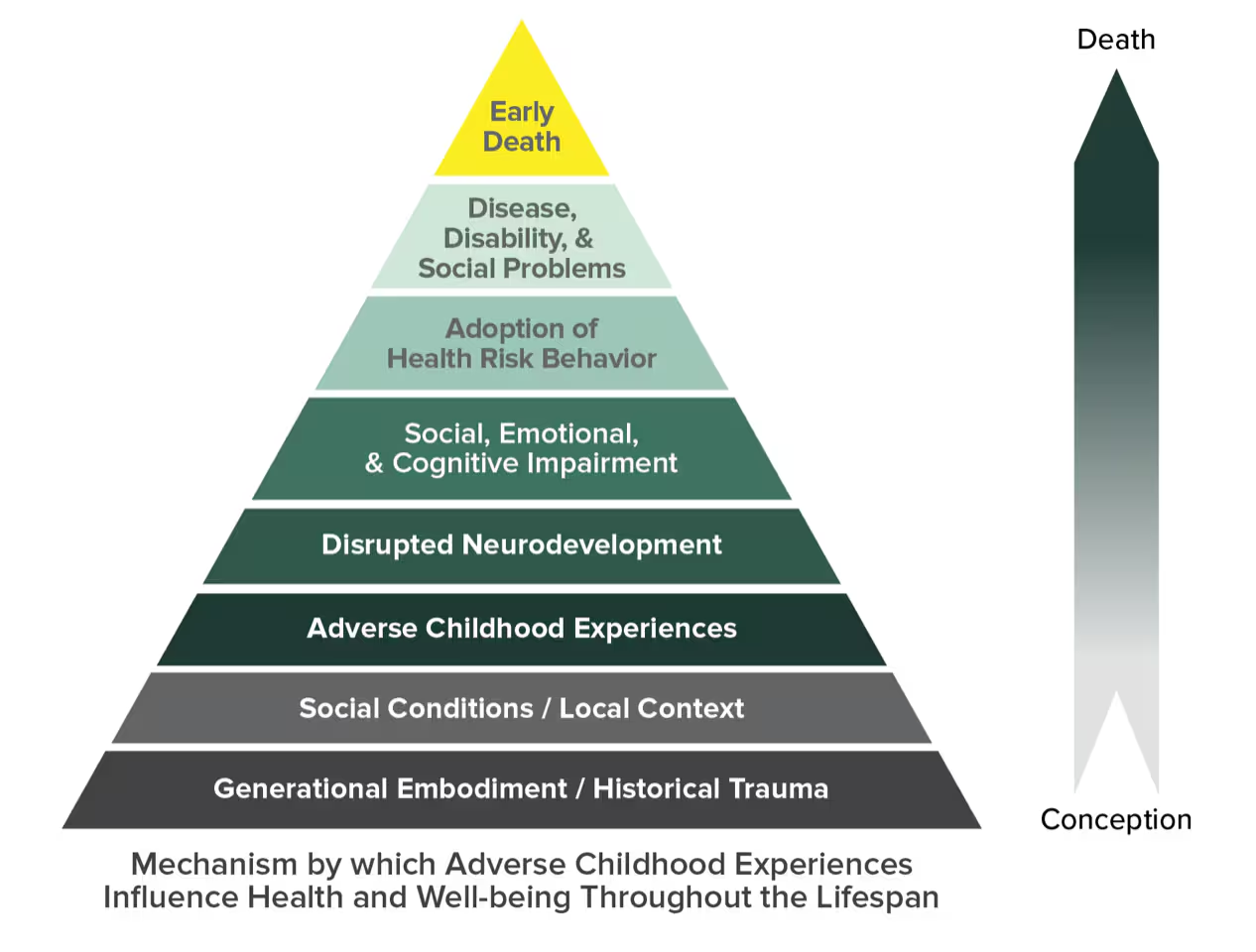

As states begin to pivot past the COVID-19 pandemic, Governors and senior state leaders are analyzing lessons learned from youth engagement in detention, while continuing to rethink the future of their juvenile justice systems. Recent research on adolescent brain development shows that the human brain continues to develop and mature throughout adolescence, even into the 20s. Compared with adults, youth and young adults are more susceptible to negative peer influences and are more likely to overreact to situations. Youth and young adults also are more likely to engage in risky behavior because their prefrontal cortex, which governs executive functions, reasoning and impulse-control, is not fully developed. With these facts in mind, state leaders, youth-serving organizations and advocates have worked to understand and apply brain science research to ensure juvenile justice systems are better able to meet the unique needs of youth and young adults. Many juvenile justice reform movements not only emphasize decarceration of children, youth and young adults, but also prioritize improvements to confinement conditions while investing in community-based alternatives to youth confinement.

State Strategies To Address The Needs Of Justice-Involved Youth Impacted By Collateral Consequences

In 2022, NGA conducted a series of learning calls and hosted a virtual roundtable to better understand the range of consequences youth may face as a result of interaction with the juvenile justice system. A paper was then developed that details the discussions and conclusions reached about the impact of these consequences on both youth and their families. The paper includes policy strategies for reducing collateral consequences and considerations for Governor’s offices and state administrative agencies when implementing these policies.

There is growing movement to right-size juvenile justice systems to better meet the developmental needs of youth and young adults by examining the parameters of juvenile court jurisdiction. In recent years, several states have modified the upper age boundary of juvenile court jurisdiction, known colloquially as “raise-the-age” policies. A total of 47 states have amended laws that define “minors” for the purposes of juvenile court jurisdiction, as persons up to age 18.

This brief focuses on emerging trends in raise-the-age efforts across states, including: (1) raising the maximum age of juvenile court jurisdiction beyond 18, (2) raising the floor, or minimum age, at which a person can be processed through juvenile courts; and (3) amending the transfer laws that limit the extent to which youth and young adults can be prosecuted in adult criminal court jurisdiction.

Key Takeaways

Recent changes in juvenile justice policies offer Governors with the following key considerations:

- A preponderance of scientific research supports setting or raising age boundaries to developmentally appropriate levels.

- Bolstering developmentally appropriate responses and care to youth and young adults can decrease recidivism and promote long-term community well-being and safety.

- States should consider data on youth and young adult caseloads, trends in disposition, the continuum of care ranging from community supports to out-of-home care and residential placement, and the availability of services and supports for young people who have committed more serious offenses as they examine age boundaries in their juvenile court systems.

- State policy efforts are trending toward both limitations and extensions of juvenile court jurisdiction.

- Such changes have fiscal impacts. It can be more prudent to fund a period of study upon implementation.

Emerging trends in raising age boundaries

The Ceiling: Raising the Age Beyond 18

Research shows that there is no clear age at which a person can think and reason as an adult: The prefrontal cortex, which moderates risk-taking, continues to develop into the mid-20s, and emotional and social factors are more likely to influence a young person’s cognitive functioning than that of an adult. Accordingly, officials in several states are considering extending the upper age limits of juvenile court jurisdiction beyond age 18 to include emerging adults or young people through their early 20s. As of 2021, three states, Vermont, Michigan and New York, have raised the age of maximum juvenile court jurisdiction to 18, meaning that a young adult can remain under the purview of juvenile courts until they turn 19. Vermont’s Act 201 of 2020 allows for further age expansions of juvenile court jurisdiction to include 19 year olds in 2022.

The Floor: Raising the Minimum Age of Juvenile Prosecution

States are increasingly setting a minimum age at which youth and young adults can be processed through juvenile courts, but there is significant variation in the minimum age established in statute, offenses excluded from minimum age requirements, and the discretion afforded to prosecutors and judges. Twenty-three states have set a minimum age of adjudication in juvenile court through statute. In these states, children under the minimum age of juvenile court jurisdiction are often served through social service and child welfare systems rather than juvenile courts. Minimum ages in these states range from 6 to 12 and statutory exceptions vary. For example, a Washington statute sets the minimum age of prosecution at 8, but to charge children between 8 and 12 in juvenile court, state prosecutors must prove that they “have sufficient capacity to understand the act.”

Conversely, the minimum age of prosecution in California is 12, but the state excludes certain serious crimes from minimum age restrictions. Twenty-seven states currently do not set forth a minimum age of prosecution through statute; however, several states recently have introduced some form of legislation related to the minimum age of juvenile prosecution. In states without a statewide statutory minimum, prosecutors and judges often have discretion about whether to process young people through juvenile courts or to refer them to social service systems. This discretion often revolves around the severity of the offense, accountability and public safety concerns, and the treatment needs of the youth.

Minimum Age of Juvenile Adjudication

| Age | Jurisdiction |

|---|---|

| None specified | 27 states: Alabama, Alaska, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawai‘i, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming |

| 6 | 1 state: North Carolina |

| 7 | 2 states: Connecticut, New York |

| 8 | 1 state: Washington |

| 10 | 15 states and territories: American Samoa, Arkansas, Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nevada, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin |

| 11 | 1 state: Nebraska |

| 12 | 3 states: California, Massachusetts, Utah |

Transfers from Juvenile to Adult Court Systems

While most states’ raise-the-age efforts have focused on expanding juvenile court jurisdiction up to the age of 18, laws allowing discretionary prosecution of youth and young adults in adult criminal court can limit these expansions. Thus, increasingly, state legislatures are turning to statutes to to address minimum transfer ages. However, the specifics vary significantly across states. Some major areas of variation include which system actors have discretion over transfer decisions (e.g., judges or prosecutors) and which crimes are excluded from an age minimum (usually crimes of violence), as well as other factors beyond age that prosecutors are required to consider.

As of the end of the 2018 legislative session, 28 states statutorily specify the age at which a youth may be transferred from an adjudication process in juvenile court to adult court. For states with defined transfer ages, these transfer allowances vary from 10 to 15 years of age, with an average transfer age of 13.

Furthermore, while a statute may determine the minimum age at which a transfer may be considered, judicial discretion still often plays an active role. As of 2016, statutes in 46 states stipulate that “the juvenile court judge makes the decision at a hearing before a minor can be tried as an adult.” Additionally, 14 states had statutes allowing the prosecutor “to decide to file charges in juvenile or criminal court as an executive branch decision due to [overlapping] jurisdiction over specified age-bound offense categories.” In 2018, “California became the first state in the country to limit transfer eligibility to only 16- and 17-year-olds,”meaning youths 15 and younger must be adjudicated in juvenile court.

Minimum transfer age specified in statute, 2018

| Age | Jurisdiction |

|---|---|

| None specified | 23 states, territories and federal districts: Alaska, Hawai’i, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Arizona, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Indiana, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maine, Rhode Island, Delaware, Maryland, District of Columbia |

| 10 | 2 states: Iowa, Wisconsin |

| 12 | 3 states: Colorado, Missouri, Vermont |

| 13 | 5 states: Illinois, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New York, North Carolina |

| 14 | 15 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, Tennessee, Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Michigan, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Dakota, Utah, Kansas |

| 15 | 3 states: Connecticut, New Jersey, New Mexico |

| 16 | 1 states: California |

“In my administration, we have stressed the need to provide education opportunities for our children and teens who are in the detention system. Our system is meant to rehabilitate young people, not to punish them.”

–Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson

The Impact of Age Reforms on Juvenile Justice Systems

Age reforms are aimed at right-sizing state juvenile justice systems by tailoring interventions to age- and developmentally appropriate venues that both maximize child well-being and promote effective resource allocation. State leaders can utilize research to support limitations on children, youth and young adults’ exposure to juvenile and adult criminal courts that align notions of culpability for criminal behavior with the latest developments in the science of adolescent brain development.

Revisions to age boundaries in the juvenile justice system are often accompanied by comprehensive system changes to maximize effectiveness. In particular, states may wish to consider the impact of changing jurisdictional age boundaries on the budgeting process for both justice systems and social services overall. As youth may be shifted away from juvenile justice systems, funding may need to be shifted to ensure adequate resources for juvenile justice systems and social services systems. Likewise, when youth are excluded from the juvenile justice system entirely, savings for the juvenile justice system may shift costs to other upstream programs in the child welfare system. When considering significant changes to age boundaries and justice system parameters, states may find value in formally evaluating the impact of such policy changes.

Upper Age Boundaries: Vermont

With its Act 201 of 2020, Vermont became the first state in the nation to expand juvenile court jurisdiction to include 19yearolds. In preparing to implement Act 201, the Vermont Department of Children and Families, in partnership with the Columbia University Justice Lab, found that: 1. overall cases involving emerging adults were declining; 2. 18- and 19-year-olds committed offenses similar to their younger peers; 3. the majority of cases involving emerging adults were low-level and should be considered for diversion from the system; and 4. almost half (40 to 45 percent) of 18- and 19-year-olds convicted in adult courts have a fine-only disposition with no supervision. These findings bolstered support for age expansions prior to the act’s passage. However, as Vermont has begun implementing Act 201, the state has encountered a number of unintended consequences, including the intersection of raised age boundaries with public information laws. In addition, challenges related to services for, and identification of, those who committed more serious crimes have underscored the need for proper systems planning and broad system reform prior to further age expansions.

Minimum Age Boundaries: California

California is the only state where a child under the age of 16 cannot be tried as an adult for any crime. In 2018, California SB 1391 raised the age of judicial transfer to 16, meaning that youth 15 and under cannot be transferred to adult courts. California also passed sweeping legislation to prevent youth and young adults initially charged in juvenile courts from being transferred to adult courts. SB 823, passed in 2020, stipulates that young adults whose cases originated in juvenile courts can remain in juvenile facilities until they are 21, pending disposition of their cases. Youth who committed more serious offenses but were committed to a post-disposition program through a juvenile facility can remain in those facilities until they reach age 25.

Transfer Laws: Missouri

In Missouri, juvenile court judges have discretion on the transfer of youth ages 12 to 18 from juvenile court to adult criminal court. A young person under 12 shall not be transferred to an adult criminal court. If the offense alleged “would be considered a felony if committed by an adult,” a hearing is triggered: The court may grant a motion by the court or by the juvenile officer, the child or the child’s custodian to order a hearing on whether the case should be transferred to an adult criminal court. If a petition alleges that a child between the ages of 12 and 18 has committed an offense that would be considered a felony if committed by an adult, the court may, upon its own motion or upon motion by the juvenile officer, the child or the child’s custodian, order a hearing and may, in its discretion, dismiss the petition and such child may be transferred to the court of general jurisdiction and prosecuted under the general law; except that if a petition alleges that any child has committed an offense which would be considered first degree murder under section 565.020, second degree murder under section 565.021, first degree assault under section 565.050, forcible rape under section 566.030 as it existed prior to Aug. 28, 2013, rape in the first degree under section 566.030, forcible sodomy under section 566.060 as it existed prior to Aug. 28, 2013, sodomy in the first degree under section 566.060, first degree robbery under section 569.020 as it existed prior to Jan. 1, 2017, or robbery in the first degree under section 570.023, distribution of drugs under section 195.211 as it existed prior to Jan. 1, 2017, or the manufacturing of a controlled substance under section 579.055, or has committed two or more prior unrelated offenses which would be felonies if committed by an adult, the court shall order a hearing, and may in its discretion, dismiss the petition and transfer the child to a court of general jurisdiction for prosecution under the general law. Further, if the alleged offense is one of several more serious violent crimes or certain serious drug offenses, the hearing is mandatory. To guide the transfer decision, a written report is prepared, which, statutorily, must include consideration of several criteria, including racial disparities in certification.

Transfer Laws: Utah

Much of Utah’s work in juvenile justice stems from legislation that created a multi-agency juvenile justice working group. This group included representation from legislators, judges, state agency directors, police chiefs, defense attorneys, education stakeholders and prosecutors. After conducting comprehensive studies, roundtable discussions and focus groups, the working group provided policy recommendations to promote public safety, limit costly out-of-home placements, reduce recidivism, and improve outcomes. This work laid much of the foundation for the state’s juvenile justice system changes. Utah is one of the few states to pass laws narrowing or eliminating automatic transfers by judges, prosecutors or statutory exclusions. In March 2020, then-Governor Gary Herbert signed HB 384 that aligned adjudicatory policy with scientific research showing that cognitive reasoning is not fully developed until around age 25. The bill sought to; all other charges require some judicial review before a transfer to adult court can be authorized. This law also provides guidance for judges to consider when determining the appropriate setting in which to hold children, youth and young adults being tried as adults; however, it does not eliminate jails or other adult detention facilities. HB 1002, enacted in May 2021, provided that all youth awaiting adjudication on an adult charge (whether through transfer or direct file) will be housed in a juvenile facility, up to the age of 21. In addition, all youth adjudicated as adults who are given prison sentences, will be housed in a juvenile facility up to age 21.

Other Age Boundaries: Mississippi

Another option for states to consider is imposing age boundaries on certain consequences resulting from delinquency adjudication. Mississippi recently passed S.B. 2282, which excludes children under the age of 12 from commitment to the state training school, and requires a delinquency adjudication for a felony in order for a child to be committed to the training school at any age. Under this law, even in the cases of commitment to a detention center, the disposition order committing the youth or young person is required to include the following findings: that the disposition is the “least restrictive alternative appropriate to the best interest of the child and the community,” that the individual will remain in reasonable proximity to his or her family given the alternative dispositions and best interest of the child and the state, and that the court has found that the detention center is equipped to provide the “medical, educational, vocational, social and psychological guidance, training, social education, counseling, substance abuse treatment and other rehabilitative services required by the child.”